BY LETTER

Pyrohydrothalassic

Hot Water Superterrestrials | |

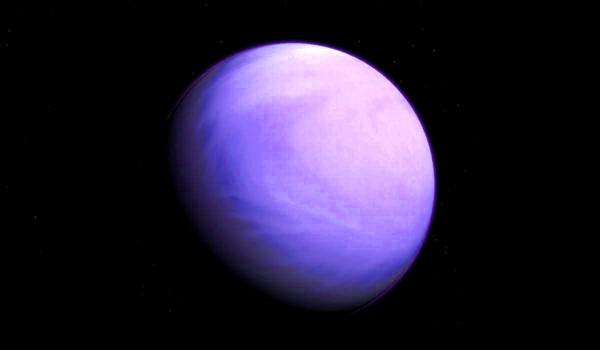

Image from Steve Bowers | |

| Atlas, a pyrohydrothallassic (hot-water) world | |

Large Water worlds covered in a deep ocean and with a high surface temperature, higher than 100° C. They occupy a middle ground between Panthalassic (cool-water ocean worlds) and pyrothalassic (magma-ocean worlds). Terrestrial-sized hot water worlds are known as PelaCytherean Subtype worlds.

The water layer may be hundreds of kilometres deep; on many such worlds the water is deep enough to compress the water into high-pressure ice, forming an ice mantle which covers the rocky layers below. The depth at which this ice mantle forms depends on the temperature of the ocean, which depends in turn on the heat received from the local star(s), tidal heating and radioisotope decay in the core.

The water oceans on these worlds remain liquid because of high atmospheric pressure; in many cases this pressure and temperature is sufficient to cause the formation of a supercritical fluid layer between the gaseous atmosphere and the liquid ocean. The supercritical fluid layer acts like both water and steam, dissolving solids without forming an easily definable liquid surface. Heavier-than-water vessels cannot float on the surface of such a layer, so explorers must use powered flight or balloons for support.

Protein-based life can only survive on the coolest pyrohydrothalassic worlds; above 200° C any colonsation effort must use artificial life-like processes, often derived from thiogen biochemistry. Due to volcanic activity within the ice mantle layers the oceans of these worlds often contain a rich mix of dissolved ions and gases, and colonies on such worlds generally base their economy on mineral extraction technology.

Related Articles

Appears in Topics

Development Notes

Text by Steve Bowers

Initially published on 22 February 2012.

Initially published on 22 February 2012.